Connecticut College Professor: "Global Warming could drastically change earth's ecology"

NEW LONDON, Conn. - Forty-eight million years ago, during a period of intense global warming, the world's tiniest warmth-seeking organisms migrated north, adapted and survived, according to new findings recently published in the March issue of PALAIOS, a bimonthly academic journal on the earth's history as documented in paleontological and sedimentological record.

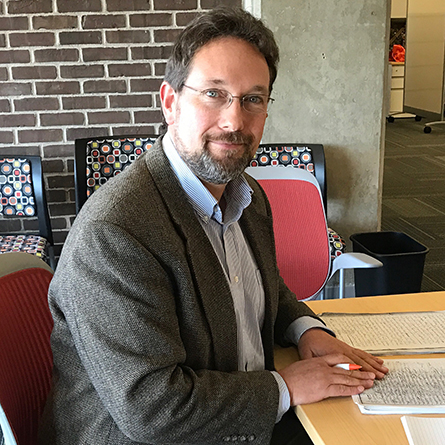

The study - co-authored by Peter Siver, director of the Environmental Studies Program and a member of the botany department at Connecticut College, and Alexander P. Wolfe, professor of earth and atmospheric sciences at the University of Alberta, Canada - indicates that a similar process going on today could indicate the beginning of another huge shift in the planet's ecological profile.

"Our findings support the hypothesis that warmth-loving organisms will be able to migrate to northern latitudes and that polar regions will become inhabited with temperate, subtropical and possibly tropical species," said Siver. "We suspect that some organisms adapted to cooler climates will either change or become extinct, but others will flourish and evolve."

The findings, published under "Tropical Ochrophyte Algae from the Eocene of Northern Canada: A Biogeographic Response to Past Global Warming," come from Siver and Wolfe's recent work on an ancient lake core from the cold tundra of northern Canada. There, within the bowels of a diamond mine some 400 feet below the earth's surface were the remains of an ancient lake, where Siver sampled mud dating back 48 million years. Viewing the mud sample under an electron microscope, Siver discovered several microorganisms identical to those that today exist in the tropics.

"I knew I was looking at the oldest know specimens ever seen for a number of different organismal groups. I felt privileged to be the first scientist to catch a glimpse of these organisms from the distant past," said Siver, who, along with Wolfe, was able to secure the core samples through a diamond mining company who originally drilled the cavernous mine and made it available for study.

The discovery by Siver and Wolfe showed that while these tiny organisms generally live in tropical climates, they were able to exist in Northern Canada during this period - when that area grew 14 degrees warmer than it is today. The "ancient warm hothouse period," as Siver called it, is significant in terms of the planet's growth in ecological diversity. During this period, there was far less difference in temperature between the poles and the Equator, meaning the planet probably lacked ice, and - for periods of time - the surface of the Arctic Ocean was undoubtedly freshwater, Siver noted.

At Connecticut College, Siver specializes in limnology and phycology and teaches courses in introductory botany, environmental studies, phycology and aquatic ecology protists. He received his doctorate from the University of Connecticut.

About Connecticut College

Situated on the coast of southern New England, Connecticut College is a highly selective private liberal arts college with 1900 students from all across the country and throughout the world. On the college's 750-acre arboretum campus overlooking Long Island Sound, students and faculty create a vibrant social, cultural and intellectual community enriched by diverse perspectives. The college, founded in 1911, is known for its unique combination of interdisciplinary studies, international programs, funded internships, student-faculty research and service learning.

For more information, visit www.conncoll.edu.

-- CC --

April 3, 2009