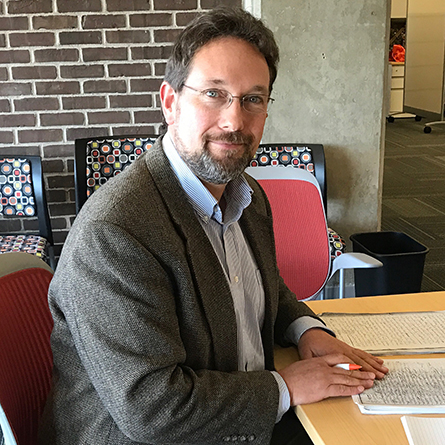

New book co-authored by Connecticut College's Anthony Graesch reveals fascinating details about life at home for today's average family

Connecticut College anthropology professor Anthony Graesch has co-authored a new, non-traditional book that throws open the doors of 32 dual-income middle-class families to give readers an in-depth look at life at home in the 21st century.

Richly illustrated with more than 250 color photos and maps, insightful observations, statistical information and quotes from the everyday people featured in the book, "Life at Home in the Twenty-First Century" is a handsome large-format book that makes a 10-year, intensive ethnographic research project accessible - if not downright addicting - to the average reader.

"As part of a large study of dual-income households with children, we set out to systematically document the material worlds of modern families," Graesch said. "Few social scientists have ventured into everyday American homes to study the ways that we interact with our houses and their contents, and this book is all about turning the anthropologist's gaze back onto ourselves, presenting that which is otherwise familiar and commonplace in such a way that it becomes unfamiliar and quite extraordinary."

Lead author Jeanne E. Arnold, professor of anthropology at the University of California, Los Angeles, teamed with Graesch and two other researchers, photographer Enzo Ragazzini and UCLA Professor of Anthropology and MacArthur Fellow Elinor Ochs to document the every move of 32 sets of working parents and their children for one week as part of UCLA's Center on Everyday Lives of Families (CELF) project, with the goal of learning about how the country's fast-growing household demographic approaches daily life. The resulting 20,000 images, hundreds of hours of video footage and rich observational data tell a story of American consumerism, evolving family dynamics and the importance of time management and use of space.

"People's homes are a canvas for self-expression, so it is crucial to see what middle-class America buys, cherishes and displays at home, along with, in their own words, what their possessions mean to them," Arnold said. "We measured. We photographed. We filmed. We interviewed. We gave parents and older kids cameras and they gave us narrated home tours. We now know what goes on moment-by-moment and, as our book documents, we know exactly what people keep in their homes and where and how they use things."

Graesch, a professor at Connecticut College since 2010 who specializes in archaeological anthropology, said the way the American middle class accumulates and interacts with material goods is particularly intriguing. "From a long-term historical perspective that only archaeology can afford, the average family has never owned as much 'stuff' as we do in the present," Graesch said. "The sheer volume and variety of objects in our homes is completely unprecedented."

One photograph, for example, shows a little girl's elaborate display of Beanie Babies (165, to be exact), along with 36 figurines, 22 Barbie dolls, 23 other dolls, one troll and one miniature castle. Other photos depict music collections that span entire walls, garages packed with boxes, bikes and old furniture, and refrigerators plastered with everything from family photos to advertisements for 1-800-PetMeds.

"We have so much stuff crammed into our houses, and it was interesting to see how this excess creates stress," Graesch said. "We know we have too much, but we don't have time to deal with it, and we can't seem to part with it. Readers will be hard-pressed to not connect consumption patterns evident in American home assemblages to broader social and environmental concerns."

The researchers also examined the families' use of space by documenting their whereabouts every 10 minutes.

"Over and over, the kitchen emerged as the most intensively used space by both parents and children," he said. "When you factor in how much time we spend at work, school and daycare, the family only gets to spend about four waking hours together, and the kitchen is the place in which we congregate, the place around which weekday life pivots. Parents are using myriad objects in these spaces, including modest kitchen tables, clocks, calendars, cork boards and objects on the cluttered surfaces of refrigerators, to socialize children into the middle-class ideals of time management and allocation."

The bathroom is also a great place to study the family dynamic, "especially if there is only one in the house and everyone is trying to get ready for work and school at the same time," Graesch said. "Small bathrooms in small houses are these incredible sites of child socialization where children learn how to be part of the family and how to share space."

Each of the families in the study had at least two children, with one in fourth or fifth grade. All of the participating families owned their home or had a mortgage on the home, and each parent worked at least 30 hours per week outside the house. Household income typically ranged between $50,000 and $150,000, and the chosen families self-identified as white and of African, South Asian, East or Southeast Asian and Hispanic descent. The study also included two dual-father families.

Graesch said that while all of the families are from the Los Angeles area, information throughout the book shows that they are, in many ways, very representative of average families from across the country.

"We made a concerted effort to situate these 32 families against a backdrop of social and economic trends in the United States and beyond," he said. "Some aspects of their everyday lives may be unique to southern California, but most Americans will recognize their own homes and families in this distinctly visual ethnography."

July 12, 2012